(c) Stephen Wilen Feb 2020 [Excerpt from Classic Yachting]

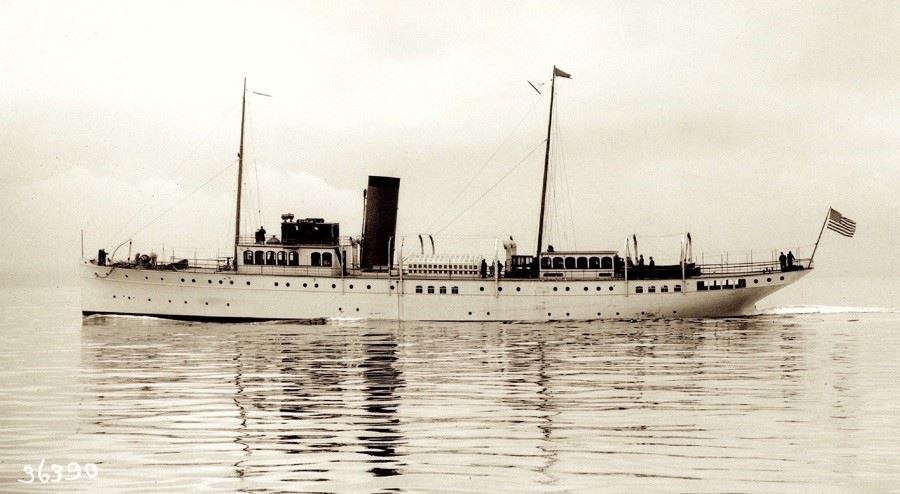

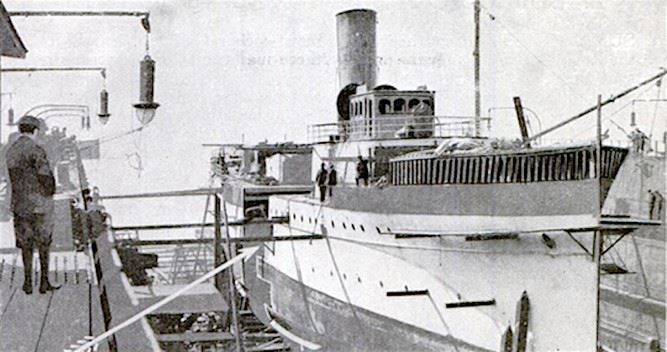

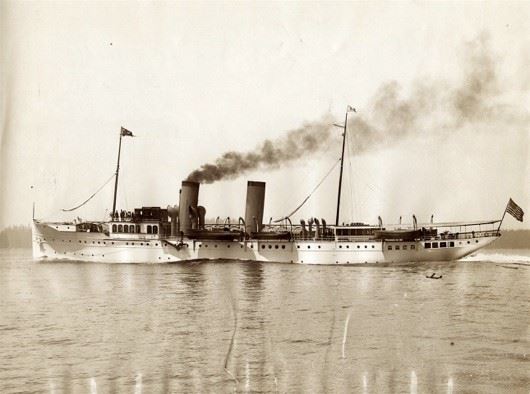

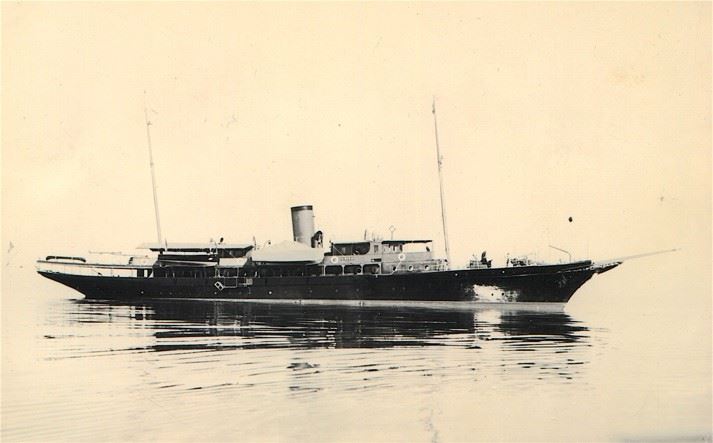

Cyprus on sea trials in Puget Sound, Washington, 1913, in her original configuration by Irving Cox of Cox & Stevens. Puget Sound Maritine Historical Society photo, 694-5.

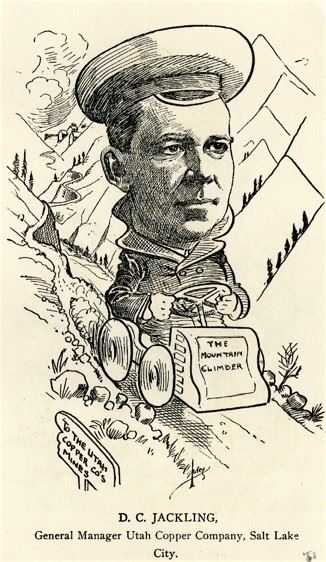

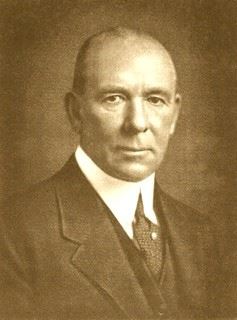

In 1912, 42-year-old Col. Daniel Cowan Jackling of Salt Lake City decided to become a yachtsman. By anyone’s account, Col. Jackling (1869-1956) was a highly complex, accomplished and extremely wealthy man. (1) Among numerous achievements he accomplished by the time he was in his 30s, he was president and general manager of the Utah Copper Company that he founded in 1903 and which became the largest firm of its type in the world. When Utah Copper was established many mocked it as “Jackling’s Folly,” but by 1910 the company was producing close to one-half of the world’s copper. Its Bingham Canyon copper pit was the world’s greatest man-made crater. Col. Jackling ran the company until 1923 when, as a consequence of Kennecott-involved Guggenheim financing, it became a division of Kennecott Copper Corporation, a marriage not completed until 1936 and one that greatly vexed the colonel. Jackling’s once-controlling role as head of Utah Copper was continually marginalized by Kennecott corporate bureaucrats in New York, culminating in his forced retirement in 1942, an embittered man. Jackling was also general manager and chair of the executive committee of the Ray Consolidated Copper Company in Arizona, and president of the Nevada Consolidated Copper Corporation.

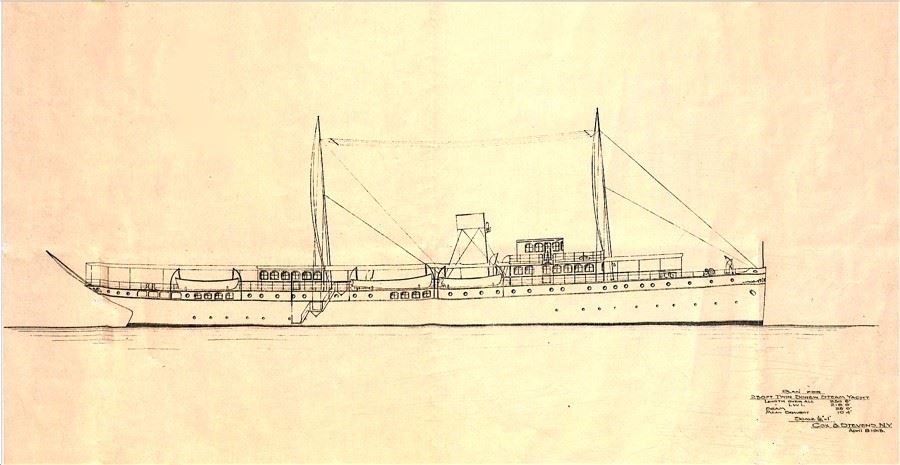

Having made the decision to experiment with yachting, as reported in the September 1914 issue of The Marine Review, Col. Jackling determined that “by experience with a not too large or costly yacht just exactly what he would ultimately require in the way of a larger vessel to meet his permanent needs.” If he was inexperienced in this undertaking, as might be assumed was the case, he surely engaged proficient advisors. Jackling did not select a yacht designer from the yellow pages of the Salt Lake City telephone directory; he went right to the top, Cox & Stevens, the prominent yacht design and brokerage firm in New York City, founded in 1905. As his trial yacht to test the waters, Jackling gave carte blanche to Irving Cox to design a steel hull steam yacht with a LOA of a “not too large” 231 feet, LWL of 215 feet, beam of 28 feet and draft of 12.5 feet. At the time of her launching in 1913, she was the largest yacht ever constructed on the west coast, a title one wonders if she still holds. (A Google search did not find any other yachts constructed on the west coast to date exceeding even her original LOA, let alone her extended LOA, to be discussed following.) (2)

Having made the decision to experiment with yachting, as reported in the September 1914 issue of The Marine Review, Col. Jackling determined that “by experience with a not too large or costly yacht just exactly what he would ultimately require in the way of a larger vessel to meet his permanent needs.” If he was inexperienced in this undertaking, as might be assumed was the case, he surely engaged proficient advisors. Jackling did not select a yacht designer from the yellow pages of the Salt Lake City telephone directory; he went right to the top, Cox & Stevens, the prominent yacht design and brokerage firm in New York City, founded in 1905. As his trial yacht to test the waters, Jackling gave carte blanche to Irving Cox to design a steel hull steam yacht with a LOA of a “not too large” 231 feet, LWL of 215 feet, beam of 28 feet and draft of 12.5 feet. At the time of her launching in 1913, she was the largest yacht ever constructed on the west coast, a title one wonders if she still holds. (A Google search did not find any other yachts constructed on the west coast to date exceeding even her original LOA, let alone her extended LOA, to be discussed following.) (2)

To build this vessel, Seattle Construction and Drydock Company was chosen (3). Although Jackling had business that took him to the West Coast periodically, including north to Alaska where Kennecott had operations, it may not be simply coincidence that his having been vice chair of the Utah Commission of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, Seattle’s first world fair held on the campus of the University of Washington in 1909, may have influenced his decision to have the yacht built in Seattle. Cost of construction was reportedly $500,000.

The completed yacht had a plumb bow, a counter stern and a graceful sheer. Col. Jackling had his new yacht christened Cyprus from the ancient Greek khalkos or kyprios, meaning ore, copper or bronze. She was the first steam yacht built to burn fuel oil. Powered by two four-cylinder triple expansion vertical inverted reciprocating engines built by Seattle Construction and Drydock Company, she had a total of 3,500 horsepower. She had four Babcock & Wilcox boilers with a total heating surface of 10,000 feet that supplied steam at 225 pounds pressure. Astoundingly, all machinery was installed in duplicate to preclude immobilization at sea. Fuel oil capacity was 260 tons. Her two scews were three-bladed, eight feet, four inches diameter with a pitch of nine feet, eight inches, giving Cyprus a cruising speed of 18 knots.

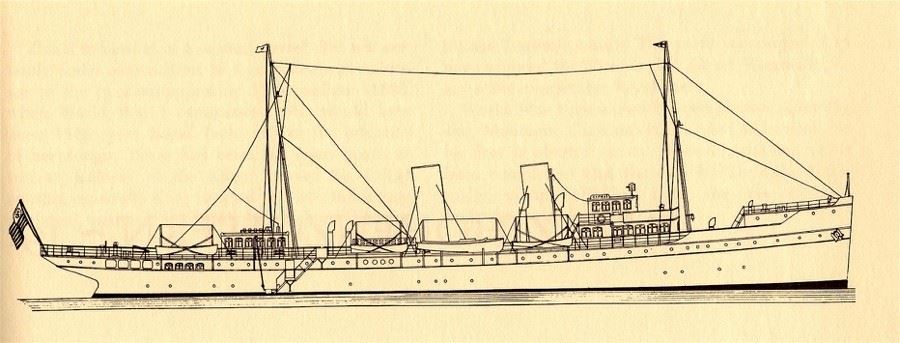

Line drawing by Cox & Stevens of Cyprus in her original configuration, 1913. Daniel Cowan Jackling papers, 1911-1956, Stanford University Archives.

The yacht had nine watertight transverse bulkheads. An auxiliary dynamo was capable of lighting the entire vessel, including two powerful searchlights, and the wireless equipment. Ample battery backup could maintain the electrical system when the dynamo was not being used. A large cold storage plant, a complete telephone system, call bells, and hot and cold water, both fresh and salt, were featured throughout the yacht.

Cyprus carried one large lifeboat and three 22-foot launches, one of which was high speed, the other two being heavy service boats.

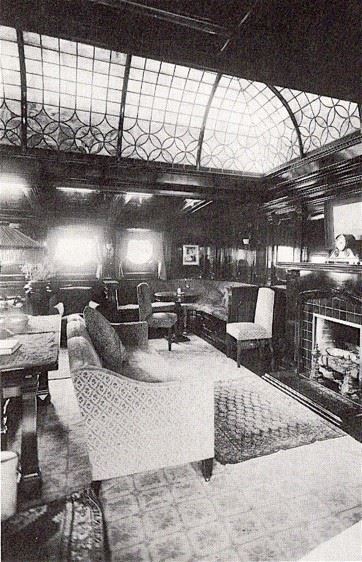

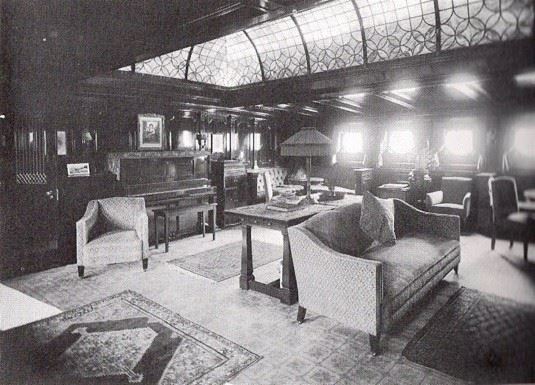

Palatial does not begin to do justice to the accommodations onboard Cyprus. In addition to the owner’s full-width stateroom with fully equipped bath, located forward on the main deck, Cyprus featured ten other master staterooms with shared baths between. A passageway between these staterooms terminated aft at a full-width music room, 21 by 26 feet containing a piano, Victrola and a massive fireplace. Overhead was an immense domed skylight of translucent glass that included an indirect lighting system to create an impression of sunlight at night. The music room had large plate glass windows one inch thick.

Abaft the music room was a library, also full width at 24 by 16 feet. The main saloon was referred to as the gunroom and was fitted out as a sporting room, displaying a variety of hunting and fishing equipment. Both of these spaces also had one-inch thick plate glass windows.

Two views of the music saloon with its huge glass dome. New York Yacht Club collection.

At the after end of this deck was a huge lounging room, 30 by 20 feet. This space was left open on the sides, protected from inclement weather by the deck overhead and the high steel bulwarks, so it was essentially an out-of-doors space.

Amidships was the galley for the crew, a bakery and a second large and well-equipped galley for the owner.

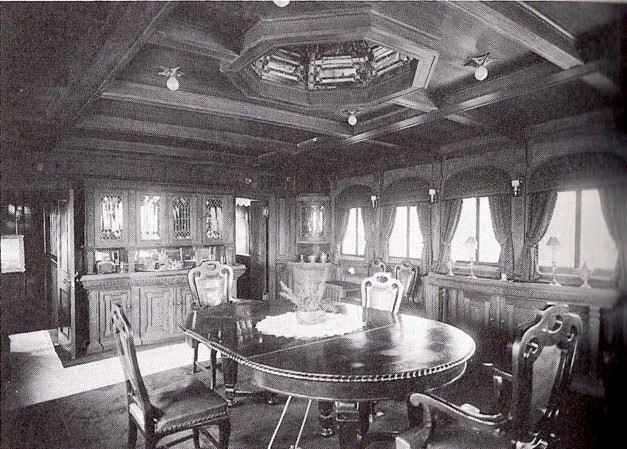

On the upper deck considerably forward was a steel deckhouse containing the dining saloon, 29 by 14 feet and a pantry. The pilothouse that appears to have been of wood construction, containing quarters for the captain, was placed atop the steel deckhouse. A smaller deckhouse abaft the mainmast, 12 by 12 feet, served as the entrance to the quarters below and contained space for the wireless equipment and operator.

Cyprus’ dining saloon. New York Yacht Club collection.

Appointments throughout the yacht were impeccable, utilizing oak and exotic woods not found on many other yachts: Tibet mahogany and India, Burma and Java teak. Surfaces not varnished or oiled were painted ivory white enamel. The overall design was described as Colonial. Bathrooms – one hesitates to use the term “head” – featured tiled floors and bulkheads.

Launched in late summer 1913, Cyprus went into commission November 20th. She carried a crew of 48, including officers, engineers, firemen, water tenders, oilers and service staff that included cooks, stewards and waiters.

Seattle’s Railway & Marine News for December 1, 1913 recorded that, “…considerable unauthorized talk had been indulged in by irresponsible parties along the [Seattle] waterfront as to the performance of the yacht on her several preliminary trials, but on the arrival in Seattle of the owner this irrelevant gossip was quickly suppressed by the removal of the [initial] captain who had been engaged for the yacht.”

Following sea trials in Pacific Northwest waters, Cyprus left for her new homeport of San Francisco, most likely in December 1913, where Col. Jackling was a member of the San Francisco Yacht Club at Tiburon. (4) During the voyage down the Pacific coast she encountered one of the most severe southeasters ever recorded, but rode out the storm admirably under the command of Capt. W. E. McNelley of Seattle. Although Col. Jackling began the voyage from Seattle, because of an important business engagement in San Francisco he had to “jump ship” en route to preclude any possibility of a weather-related delay, and continue his trip on land, probably in his private railroad car that was also named Cyprus. Upon reaching San Francisco, Capt. McNelley remarked that he was “…highly pleased with the conduct of Cyprus on the trip…[she is as] worthy as they make them. I wanted to test her and we gave her a good test with bucking a very stiff southeaster all the way down. She went through like a duck…”

Conflicting with Capt. McNelley’s positive assessment of Cyprus’ voyage from Seattle to San Francisco is the inclusion in Horace W. McCurdy’s 1966 Marine History of the Pacific Northwest: “…the large ocean-going steam yacht Cypress [sic]…was found to have insufficient stability for offshore cruising, but following extensive alterations proved an excellent sea boat, making a voyage to the East Coast via Magellan Straits.” It is assumed these alterations were made as part of the lengthening of Cyprus by 35 feet, as her only known circumnavigation of South America occurred after her lengthening.

Once settled in San Francisco, Cyprus continued to cruise the Pacific Coast venturing south as far as the Panama Canal.

Railway & Marine News (op. cit.) also noted that upon reaching San Francisco Cyprus undertook a pleasure cruise to the Hawaiian Islands, returning to Seattle in February 1914 to convey Col. Jackling and business associates to visit property of the Alaska Gold Mines Company at Juneau.

* * *

Col. Jackling’s impression of his “not too large” yacht was obviously positive, and he was paraphrased in the September 1914 issue of The Marine Review as being “…not only entirely satisfied with her performance, but astonished at her remarkability to maintain a high speed at sea with entire comfort to those onboard.”

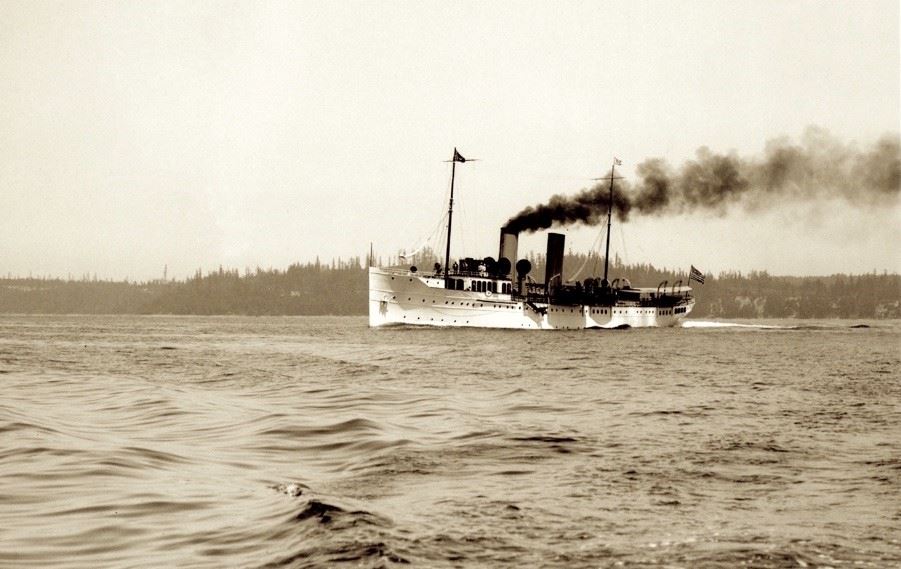

Having determined by the close of winter cruising 1913 and a brief spring and early summer cruising season 1914 that the life of a yachtsman was to his liking, Jackling decided to have Cyprus enlarged if it could be done maintaining the same amount of comfort. In consultation with naval architect Irving Cox, it was suggested that Cyprus could be cut in half amidships and lengthened 35 feet, thereby increasing desired accommodations while forfeiting minimal of her cruising speed of 17 to 18 knots. (An earlier consideration to sell Cyprus and order a new yacht had been dismissed.) Thus, a contract was signed with her original builder, Seattle Construction and Drydock Company, to accomplish this work, that appears to have been completed by late August or early September 1914.

Cyprus cut amidships. Note supports for heightening the fo’c’s’le bulwarks. Popular Mechanics, December 1914.

Cyprus’ joinery was removed first from the area where she was to be cut in half. She was then placed in drydock preparatory to cutting through the steel plating of her hull directly between her engines and boilers. A launching cradle was placed under the forward end of the yacht, strong cables were attached to the bow and the forward section was winched the precise needed distance of 35 feet, the planning having been done with such precision that only one haul was required.

Line drawing profile of the extended Cyprus from The Steam Yachts, Erik Hofman, 1970.

The lengthening allowed for the installation of additional fuel oil tanks, new quarters for 12 of the crew and three assistant engineers, plus four additional staterooms for guests. As can be seen in before and after photos, the fo’c’s’le bulwarks were heightened significantly, giving Cyprus a more distinctive profile (although compromising her sheer) while also helping to prevent substantial bow wash over the foredeck. Also adding to her distinctive profile was the addition of a second rakish funnel abaft the original funnel and just forward of the dome over the music room. The only other large American yacht with two funnels was Vincent Astor’s Noma.

Press photo by Webster & Stevens of the lengthened Cyprus on sea trials off Vashon Island, Puget Sound, Washington, July 7, 1914, with naval architect Irving Cox aboard. Author's collection.

Another photo of the lengthened Cyprus on sea trials in Puget Sound, possibly taken the same day as the previous photo. Puget Sound Maritime Historical Society photo 694-6.

Col. Jackling often conducted business while onboard Cyprus. Therefore he had his own quarters forward on the main deck at some distance from those of his guests. In addition to a full bath, a personal library opened off his stateroom, as well as a private office and an office for his secretary.

During 1915, Cyprus steamed south enabling the colonel and friends to visit mining operations along the west coast of South America. Jackling and his guests departed ship at Valparaiso and crossed the lower part of the South American continent by rail to Buenos Aires, while the yacht navigated Cape Horn. Perhaps they were concerned about a possible encounter with pirates, for which two brass guns had been mounted on the foredeck. While the yacht was not attacked by pirates, the trip was “not without excitement,” as reported in Pacific MotorBoat in July 1916, as the bridge was carried away in a storm near the east end of the Strait of Magellan, taking the pilot and first officer with it. Both men were rescued at considerable difficulty.

On June 1st, following an 83-day voyage, the yacht dropped anchor near the Statue of Liberty where she was filmed before steaming up the East River at 18 knots en route to anchorage at the 23rd Street pier of the New York Yacht Club, giving harbor workers a thrill as she passed. Col. Jackling, in resplendent yachting regalia, stood on the bridge, accompanied by his wife and 12 guests, watching the New York skyline pass by (5). Jackling maintained an office at 25 Broad Street and after attending to business in New York a second cruise along the east coast was planned.

Whether this second cruise took place is unknown, and from this point Cyprus’ history becomes hazy. H. W. McCurdy (op. cit.) notes under events of 1916 that Jackling sold his yacht to John N. Willys of the Willys-Overland Company following the voyage around South America. Pacific MotorBoat confirmed in its September 1916 issue that John Willys had entered into a contract with Jackling to purchase Cyprus for a trial run up the Hudson River, and Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly Newspaper on September 28, 1916 included a photo of Mr. Willys sitting aboard his new yacht Cyprus.

However, the Los Angeles Herald reported on April 11, 1917 that Jackling had sold Cyprus to the Russian government for the sum of $650,000 for use as a scout cruiser; this sale occurred not only during World War I hostilities, but one month after the Russian Revolution had begun. That being the case, transfer of ownership of the yacht to Willys was evidently not finalized. The Herald went on to note that the yacht arrived in New York from the West Indies where she had been under charter to steel magnate Price McKinney of Cleveland.

The New York Times on January 29, 1917, noted that a contract to convert Cyprus for the Russian navy had been awarded to Fore River Shipyard in Quincy, MA. One can only commiserate over the removal of all the luxurious appointments from Cyprus during her conversion to a Russian navy scout cruiser, and perhaps it is less troubling that little is known about that part of her life. It is not uncommon that once a vessel is sold out of American ownership tracking it often becomes laborious, if not outright impossible. In the case of Cyprus, her ownership had become rather muddied even before passing into foreign ownership.

What caused the middle-aged Col. Jackling, who, in a metaphorical sense, had belly-flopped into the world of yachting at great expense to himself (as it is to most, although Jackling’s financial commitment was astronomical), had declared himself a committed yachtsman after one cruising season, then sold Cyprus a scant two-plus years after taking possession of her? The answer to this question after more than 100 years most likely will remain an enigma.

It was reported succinctly by Lawrence Perry in an article titled They’re In the Navy Now, published in The New Country Life in August 1918 that the former steam yacht Cyprus ended her brief life “lost on the Russian coast” at less than five years of age.

A scan of all war-related shipwrecks during 1918 failed to disclose any that were definitively the former steam yacht Cyprus. On November 10th, the Admiral Kornilov was lost. It was described as a “steamer…being used as headquarters ship by General Bicherahov…destroyed by fire at Petrovsk…possibly arson/sabotage.” While a fire or sabotage would suggest the ship likely was not at sea when lost, Petrovsk is on the Medveditsa River and nearer the Caspian Sea than what would normally be described as the Russian coast. While the exact location of her loss remains undetermined, the former steam yacht Cyprus was never seen again. Sic transit gloria celox.

Col. Daniel Cowan Jackling

Col. Daniel Cowan Jackling

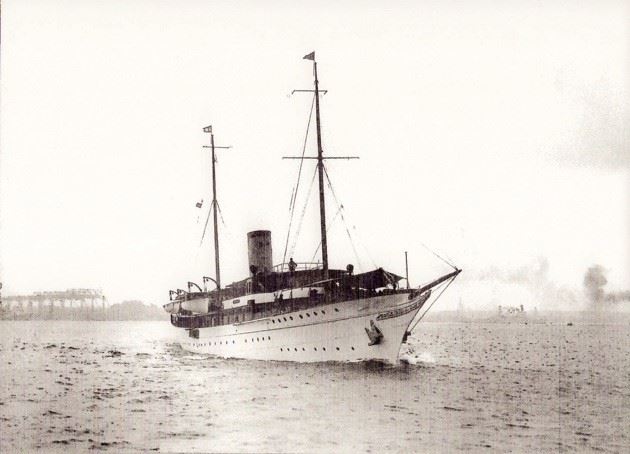

In fact, Col. Jackling’s years as a yachtsman did not end in 1917. His fourth biological cousin, Daniel Eliot Jackling, is in possession of a 12-page journal in which it was recorded that the Jacklings sailed from New York in April 1929 aboard the RMS Olympic, sister ship to the ill-fated Titanic, on a voyage that now seems apparent was to take possession of a new yacht in Germany. The journal traces a European combination land vacation through various countries with cruising onboard the new yacht, also named Cyprus that continued to March 1930 and encompassed over 50,000 miles. Bill Robinson’s 1970 book, Legendary Yachts (see reference list), has a photo of a clipper bow yacht that is not the steam yacht Cyprus, but with the name Cyprus legible on the port running board. On the same page are included three interior photos that are clearly of the 1913 steam yacht although they are presented as being interiors of the clipper bow yacht.

The second Cyprus on sea trials at Kiel, Germany, 1929, with what may well be Krupp yard cranes in the left background. Another photo taken the same day reveals that she carried what appears to be distinctly a machine gun on her foredeck.Daniel Elliott Jackman photo.

A check of the 1930 edition of Merchant Vessels of the United States revealed that in 1929 a second Cyprus was commissioned of Cox & Stevens, a 227 LOA steel diesel yacht constructed in Kiel, Germany that year. The owner was listed as International Exploration Corporation (Delaware) with an address of 25 Broad Street, the precise address of Col. Jackling’s New York office. The new Cyprus bore an amazingly similar profile to Max Fleishmann’s 218-foot Haida (see footnote 1).

Max Fleischmann’s Haida, also designed by Cox & Stevens and built by Krupp in 1929, bears a strong resemblance to the second Cyprus. Author photo.

The second Cyprus remained in Col. Jackling’s ownership slightly longer than the first Cyprus, but in 1934, by then in his mid-sixties, it seems he reached a decision to “swallow the anchor” and sold her to Italian ownership. (6) For the remaining 22 years of his life, Col. Jackling did not own another yacht.

* * *

(1) Col. Jackling was one of a small number of civilians ever granted the U. S. Military Distinguished Service Medal following, in 1916, his discovery of how to make smokeless powder. The medal was presented to him by President Woodrow Wilson on July 9, 1918. He was awarded the title of Colonel by the Utah National Guard following his participation in quelling anti-union violence against miners during the Cripple Creek, CO uprising in 1894. On April 19, 1955, the year before his death, Col. Jackling was promoted to Honorary Brigadier General in the Utah National Guard.

(2) At 218 feet LOA, the diesel clipper bow yacht Haida, built for Santa Barbara resident and yeast heir Max Fleishmann, also designed by Cox & Stevens and still in service in 2020, is a close contender for this distinction, but she was constructed in Kiel, Germany 13 years after Cyprus was launched. Haida was a frequent visitor to the Seattle Yacht Club during the 1930s. A second Cyprus, commissioned by Jackling from Irving Cox in 1929, and, like Haida, built by Krupp in Kiel, Germany, could almost be considered a sister yacht, although Jackling’s yacht exceeded Fleischmann’s by nine feet LOA. Nonetheless, it begs questioning whether Cox might have earned two salaries for what was essentially one design! It is interesting that by 1929 the clipper bow that reigned during Edwardian age steam yachts had largely been replaced by a more plumb bow for yachts well before the commissions for Haida and Cyprus.

(3) The firm had begun as Moran Bros. Shipyard, that could trace its beginnings to 1882 and whose most famous launching was the battleship USS Nebraska in 1904. The Morans sold the yard to SCDC in 1906 that in turn ceased operation in 1918, when it became Todd Pacific Shipyards Corporation. Vigor Shipyards purchased Todd in 2011.

(4) Col. Jackling’s first wife died in 1910. A daughter born of this marriage died at just one year, and Jackling, heart-broken by the death of his child, had no other children. In 1915, he moved to San Francisco, initially living in the Saint Francis Hotel on Union Square and later in a penthouse atop the Mark Hopkins Hotel. Eventually, remarried to Virginia Jolliffe, in 1925 he commissioned a large residence in Spanish Colonial style in nearby Woodside, designed by noted architect George Washington Smith. The house contained a four-manual, 55-rank George Kilgen pipe organ that had been enlarged from an earlier two-manual, 14-rank Aeolian player organ of 1930. Following the death of Virginia Jackling in 1958, the house remained largely empty and was occupied by squatters. This sad situation continued until 1984 when Steve Jobs purchased the property. Jobs leased out the mansion until 2000 when he stopped maintaining it. By 2004, it was seriously deteriorated and Jobs petitioned to have it demolished. Both the Superior Court and the State of California Court of Appeals denied permission, but in 2009 the Woodside Town Council granted permission to have the house moved to a new location, allowing Jobs to build a smaller house on the site. However, eventually, the case having been returned by the Court of Appeals, the Superior Court allowed Jobs to destroy the house. This was surely a case of demolition by neglect and does not speak well for the late Mr. Jobs. In January 2011, the pipe organ, in very poor condition by that time (a homeless man had set fire to the console in 2010), was removed and the following month the entire house was demolished.

Organist Virginia Allen at the console of the Kilgen pipe organ in 1940. Organ Historical Society pipe organ Database.

(5) If her bridge – assuming that to be the wooden pilothouse – had been swept away in the Strait of Magellan, one must ask how Col. Jackling managed to be standing on the bridge as the yacht cruised up the East River. It is questionable that a sufficient amount of time out would have been taken from the long cruise to allow repairs to be made at a shipyard somewhere between Florida and New York. Also, she was filmed in the Hudson River upon arriving in New York and the photo shows her pilothouse 100 percent intact.

(6) In the late 1930s, Cyprus (she retained her name while under the Italian flag) was under charter to the Baron Maurice de Rothschild of Paris.

References:

Daniel Eliot Jackling, Bullhead City, AZ, 4th biological cousin of Col. Daniel C. Jackling

Tim Noakes, Head of Public Services, Special Collections, Stanford University

McCurdy, H. W., Marine History of the Pacific Northwest, Superior Publishing

Company, Seattle, 1966

Robinson, Bill, Legendary Yachts, The MacMillan Company, New York, 1971

Hofman, Erik, The Steam Yachts: an Era of Elegance, John DeGraff, Inc.,

Tuckahoe, NY, 1970

Brown, Ronald C., Daniel C. Jackling and Kennecott: a Mining Entrepreneur’s

Adjustment to Corporate Bureaucracy, Mining History Journal, 2003

HistoricImages.com

Museum of History and Industry, Seattle

Puget Sound Maritime Historical Society

Organ Historical Society Pipe Organ Database

Engineering and Mining Journal, Vol. 101, no. 21, January 1916

Form: Illustrated Journal of Leisure, February 7, 1914

International Marine Engineering, September 1914

Pacific Marine Review, San Francisco, November 1913

Pacific Marine Review, San Francisco, Vol. 11, 1914

Pacific MotorBoat, September 1916

Popular Mechanics, December 1914

Sausalito News, December 20, 1913

The Marine Review, September 1914

Yachting, August 1913

The New Country Life, August 1918

The New York Times, January 29, 1917

Los Angeles Herald, April 11, 1917

Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly Newspaper, September 28, 1916

Railway & Marine News, Seattle, December 1, 1913

Merchant Vessels of the United States, United States Department of Commerce,

Washington, D.C., 1930 and 1934 editions