By George Eggerton, Canadian Fleet

Sometime a few years ago, I was down in the engine room bilge of my boat, Mysterion, struggling to resecure a bilge pump at the right height. It had come loose and had to be attached at a level that coordinated with the main bilge pump and would be easily accessible, not requiring a snorkel to locate if there were problems in future. It was hard work, in a tight space, lots of smudge all-round. And my legs weren’t as young as they used to be 79 years ago. As usual the job took more time than anticipated and, as I worked deeper and deeper into a narrowing space and as jumpy stainless steel screws kept falling into the bilge water in distressing numbers, I began to wonder if I might be stuck vertically in the shrinking space without a preplanned exit backout and without access to my cellphone, which also had a distressing habit of falling into the bilge water. Could I defy gravity and wiggle myself back to safety? How long could one survive if jammed head-first in a bilge? Should I have gone on the diet suggested by my wife many times? Suddenly I heard a gentle noise above me, a head with thick white hair peeked through the wheelhouse door, asking if I was ok. As it turned out I was ok, was able to extract myself, and the bilge pump allowed itself to be corrected and has worked well ever since. But I was grateful for the query as to my wellbeing. And I decided to go on a diet.

This was my first meeting with Bill Rhone. Subsequent meetings were under much happier circumstances. Bill has become a recognized and welcome presence at many of the marinas in Vancouver and throughout British Columbia where classic yachts and historic boats are moored.

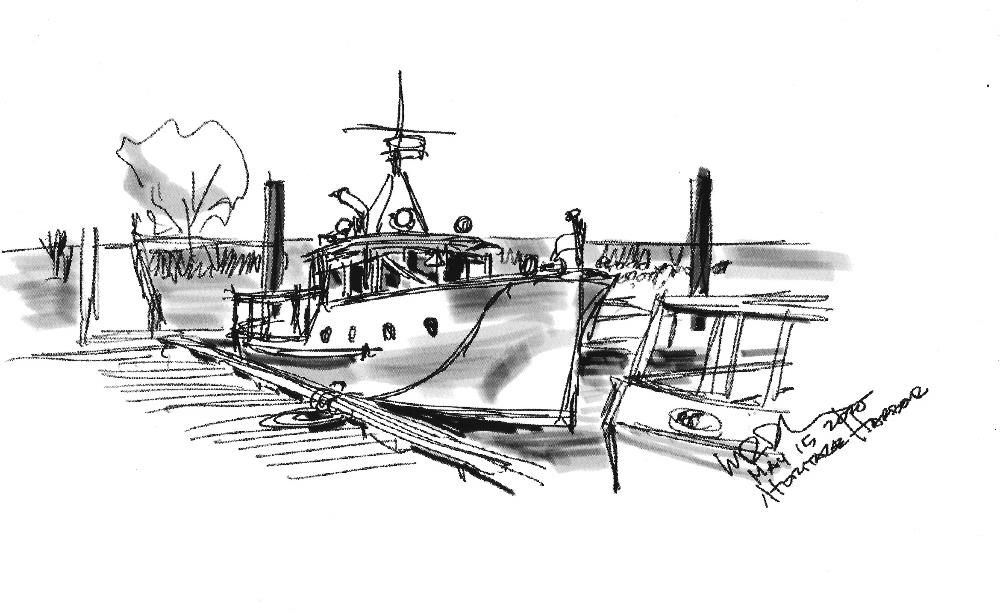

Recently, I received a brown paper envelope addressed to the owner of Mysterion. In the envelope were two beautiful sketches of my boat. (See the illustrations.) In thanking Bill for these fine pictures, I invited him for lunch on the boat, and a chance for him to view the insides. He eagerly responded positively, and we soon shared a clam chowder, spiced up with candied maple-smoked salmon while immersed in conversation, where we lost all sense of time as we discussed our interests and experiences.

Figure 11 Mysterion, Heritage Harbour

Figure 11 Mysterion, Heritage Harbour

I grew up in Winnipeg, with a love for rivers and lakes, notably Lake Winnipeg and the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. My best friend lived right on the Assiniboine, at the bottom of my street. What a magnet for learning about river life, especially during the floods of 1948 and 1950, when schools were closed, and education turned to more interesting paths. Our families had to evacuate, mine to Rabbit Lake, near Kenora Ontario, where I found I was a born-obsessive fisherman. I also of learned that fishing and boats went together, but I caught my first fish, a Northern Pike, or Jackfish as we called them, off the end of the peer at Rabbit Lake, after approximately 5000 castings. I was eight years old, but I was persistent.

After university studies in History, I took my first appointment at Memorial University in Newfoundland, in 1969, and spent two happy years there where my office had a view over the turbulent North Atlantic Ocean, and where winter blizzards sometimes left snowdrifts on my office floor. The sea was ever-present and yearly iceberg flows jolted spring warming back to winter chills. Then, in 1972, I was invited to join the History Department at the University of British Columbia, where I now had a view on the Pacific Ocean as it joined up with the mountains and the city. I soon bought a large inflatable boat for local rock cod fishing and a lot of pumping.

After some forty years of teaching more than 4000 students, research and publishing that had little to do with boats (except for the Royal Navy in the Great War), I retired from UBC in 2008, and thought it was now time to take up fishing again. So I went on-line to look for a small boat suitable for local fishing. As it turned out, my eye accidentally wandered to classic yachts for sale, at unbelievable prices after the financial crash of 2008 and the New Orleans hurricane disaster. Thank goodness for financial crashes sometimes. I looked at on-line sales of fantastically beautiful classic yachts, going for unbelievable prices, not knowing that boat is an atavistic and true acronym for ‘bring on another thousand.’ Naïve and seduced, I soon became the owner of Mysterion, built in Vancouver, launched in 1927, later moored in Blaine and La Conner, Washington, full of history, believing all my experience in amateur restoring of heritage houses could easily be transferred to restoring boats. Twelve years later, the many thousands of dollars poured into the boat, but with no regrets, were in my memory as Bill and I enjoyed our chowder on Mysterion, with restoration still an on-going process, without end, financial and otherwise.

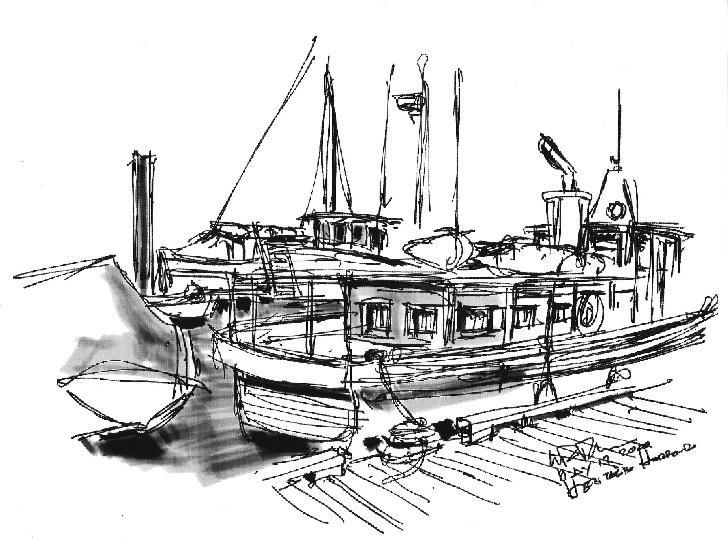

Figure 12 Mysterion moored at Heritage Harbour, Vancouver. By permission, Per Furst

Figure 12 Mysterion moored at Heritage Harbour, Vancouver. By permission, Per Furst

Bill grew up in California and took advantage of support from the American military to study architecture at the University of California, Berkeley, graduating in 1952. His deferred draft meant that he was required to put in some 21 months of military service. Being a university student in 1950 meant that he avoided being sent to fight in the Korean War. After graduation and service as a Junior Officer in the US Army, he undertook post-graduate studies in London, England. Then, in 1956 he migrated to Vancouver and with a professional partner, Rand Iredale, set up the firm Rhone and Iredale Architects in 1960. Over the next decades, this firm would flourish, when there was a powerful market for innovative architecture. Indeed, Vancouver is marked by the iconic architectural legacy of Rhone and Iredale buildings, including the Science Buildings at Simon Fraser University, the Westcoast Transmission Building, the Crown Life Building downtown, and the False Creek Housing Cooperative.

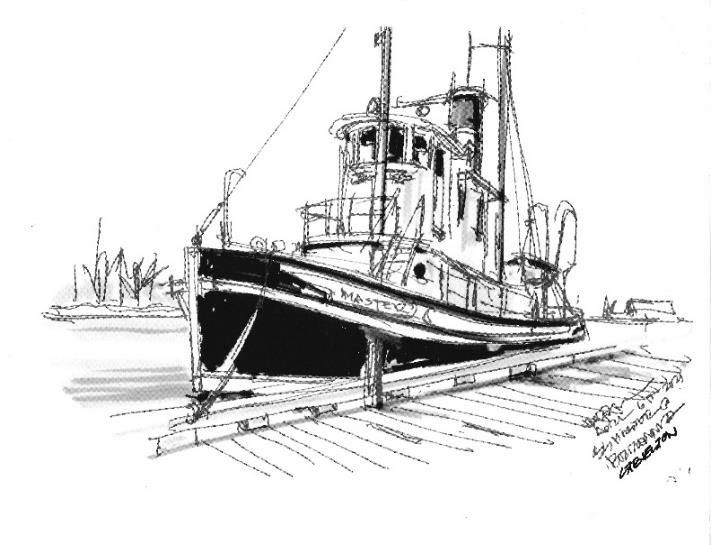

After a very distinguished architectural career, Bill was able to pursue another passion – sketching boats set in the harbors and marinas of British Columbia. Of course, sketching went hand in hand with architectural design, but when asked how long he had been sketching, the answer is most of his life. All it took to begin was a pencil and a sketch pad. But his son, a software specialist, years ago introduced him to what could be done more effectively on an iPad. Here the interest and focus could remain the same, mainly classic boats at moorage in beautiful harbours. But in various perspectives of daylight, weather, and scale, the iPad offered improvements of speed, background variations, erasure and resketching, together with easy portability and sharing.

Figure 13 Mysterion, Heritage Harbour

Figure 13 Mysterion, Heritage Harbour

In late 2020 and into 2021, the Vancouver Maritime Museum mounted an exhibition of Bill Rhone’s artwork, dozens of favorite sketches of boats set in local seaside locations. Despite the covid pandemic, the beauty of this exhibitions brought pleasure to many visitors, some recognizing their own boats as an added bonus. To share a view of Bill’s iPad gallery is to see many hundreds of sketches, each with a distinctive view and setting.

It is interesting to compare photographs of boats with Bill’s sketches. Each have their attractions: photos capture the realism, the colours, the changes overtime with restorations, and equally the weathering and deterioration which also occurs, alas. Bill’s sketches strike me as having a distinct sense of dynamism, movement, abstract lines which grip the viewer’s imagination. And happily, the image is fixed in time, defying deterioration.

Why does Bill do this? Not for any commercial result. As he says, it’s just for fun. Few artists have had so much fun, judging from the results. Readers can see for themselves from the several sketches we include with this article.

Figure 14 S.S. Master, Vancouver’s Last Wooden Steam-Powered Tugboat, Being Restored for its 100th Birthday, 2022

The above article is excerpted from the Canadian Fleet Newsletter, January 2022

The above article is excerpted from the Canadian Fleet Newsletter, January 2022